On 12 September 2021, about 3,000 people protested along the four most polluted beaches in the southern suburb of Tunis, forming a human chain along the coast. They were hoping to put an end to the disposal of off-spec wastewater in the sea.

Since the “longest human chain” in the history of Tunisia was formed, departments in charge of environmental management were expected to take action. In November, the National Sanitation Utility (ONAS) organized a public consultation regarding a sea outfall project, 7 km from the Oued Meliane delta, where a pipe would be built to transfer treated wastewater from the treatment plant to the sea.

The citizens living on these coastlines were contributing to the degradation of the sea and shores since the 1990s. Known for receiving tourists from all over the world during the holidays, the hotels of the southern suburb of Tunis were once swarming with visitors.

“Until the 1980s, in Ezzahra, swimming during the weekend was not possible because there was no room,” stated Ghazi, a 61-year old retired geologist and activist.

Ghazi, Nader, and Khaled are activists and residents of Rades, Hammam-Lif and Ezzahra. They remember the southern coast of the Gulf of Tunis before the pollution overtook its shores.

“We could see the clear water abound in biodiversity. The even clearer sand, housed shells that we can no longer find. Nowadays, we can only hope for some glimpses of clear water when currents are in favor, only alleviating some of the already murkiness of the water.”

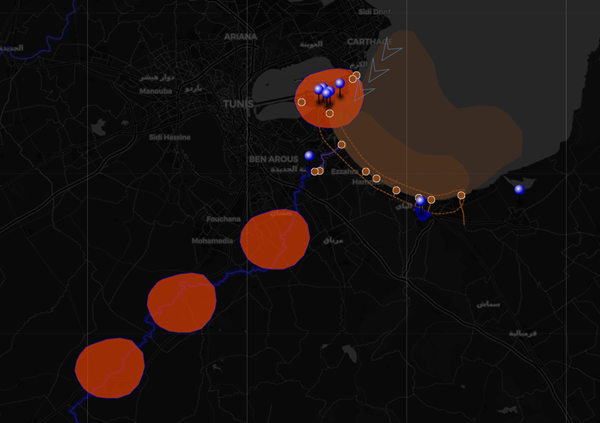

Currently, about 95,000 m3 of wastewater is treated daily in the southern suburb. A large part of this water, which is not consistent with Tunisian standards – including NT.10602 regarding the discharge of effluents into water bodies – is directly discharged into the sea in several places (see map).

An analysis conducted by Institut Pasteur upon the request of residents in the southern suburb revealed that an increase in bacterial contamination was stemming from wastewater. These findings were also supported by an analysis carried out by the Ministry of Health.

Protesters against water pollution have mainly targeted ONAS. As the only public body in charge of treating wastewater in Tunisia, the treatment of all household and industrial effluents falls under its jurisdiction. However, several groups are also involved in the Tunisian coastline: the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Territorial Planning, as well as the ministries of Environment, Health, Industry, Local Affairs, etc.

Pollution in the Gulf of Tunis has become ‘matter of fact’

Wastewater treatment systems in Tunisia are failing for several reasons, as reflected by the noticeable coastline pollution. Entire neighborhoods are disconnected from sewage systems on the bed of Oued Meliane in the villages of Rades, Mornag, Fouchana, and Zaghouan. Furthermore, in the purification plant of Rades, an industrial effluent treatment unit was damaged due to wastewater incoming from factories that failed to provide prior treatment, despite legislation in force.

Although the inspectors of the Coastal Protection and Planning Agency (APAL) and the National Environmental Protection Agency (ANPE) have the authority to end violations by factories, the set fines remain insignificant compared to the social and economic cost of the environment’s deterioration. Some industrial stakeholders have failed to follow laws that state they must have pretreatment plants. Radical measures to end these violations are yet to be implemented due to concerns over hundreds of job losses.

As for violations by the National Sanitation Utility, the fact that the three bodies fall under the mandate of the same Ministry shows a conflict of interest in the legislation, which makes the Ministry of Environment both judge and party to the issue. On one hand, ONAS pollutes, and on the other, agencies guarantee the protection of the environment.

In order to have an overview of the current situation in the coast of the Gulf of Tunis, a map was created based on satellite images, field visits, and a literature review cross-referenced with resident testimonies. It highlights the discharge points along the riverbeds into the sea, with the main industrial centers, purification plants, and sedimentation zone.

Identified sources of pollution along the coastline of the Gulf of Tunis

The premise of multi-player dialogue

To bridge the gap in public data, residents themselves have conducted analyses at the Institut Pasteur, proving that water contamination goes beyond the area defined by the Ministry of Health. According to the analyses, the main reason for water pollution is wastewater discharged by ONAS, despite the discharge coming from nearly fifty factories on the bed of Oued Meliane starting from Bir al Mashariqah. In fact, up until 2014, pollution was associated with the port, the thermal power station in Rades, and the surrounding industrial activity.

From 2013 to 2014, residents and associations of Hammam-Lif, Rades, and Ezzahra launched a series of actions. First, a petition was submitted to local and regional authorities, and the Committee on Industry, Energy, Natural Resources, Infrastructure, as well as the Environment at the Assembly of Representatives of the People of Tunisia.

In response, the Ministry of Environment signed a rehabilitation plan for the purification plant in Oued Meliane in 2016, which included only two organizations and municipalities: Zaghouan and Ben Arous – two villages far from the coast. As a result, a meeting was organized in the governorate of Ben Arous with the associations and municipalities of Rades and Ezzahra.

In January 2017, a committee was established with representatives from the Ministry of Environment, National Sanitation Utility, Ministries of Health and Agriculture, and the associations of Ezzahra and Hammam-Lif. The assessment helped identify a third source of urban pollution: the neighborhoods that are not connected to the purification plant – thus directly discharging wastewater into Oued Meliane.

A grassroots movement against pollution emerges

The existing network of associations organized an initiative on 12 September 2021 under the slogan of “United to Save our Seas and Beaches in the Southern Suburb.”

The event was launched on social media through a campaign posted on a Facebook group. Boasting 14,000 members, this group hosted a discussion on the need to mobilize between members including Jade (biologist and member of the hiking club), who suggested drawing inspiration from the human chain as means to protest.

“Within two weeks, we were able to gather over 3,000 people; imagine what we are capable of doing for the southern suburb,” said Hajer, activist in charge of coordination for the initiative.

For these activists, mobilization in the southern suburb joined similar movements undertaken by organizations in Sfax and Nabeul to save the Tunisian coastline from marine pollution. Now the challenge lies in how to organize and forge alliances on a unified front. One issue that often comes up in meetings is that movement will not be headed by any one organization – especially a new one.

Mobilization that pays

Highly publicized, this mobilization has attracted the attention of the National Sanitation Utility, which launched in the following months a public consultation on its pollution mitigation project. During the second week of November, consultations were held in four municipalities: Hammam Chott, Hammam-Lif, Rades, and Ezzahra. They were concluded with a meeting in Africa Hotel in Tunis. An environmental and social impact assessment for the outfall project was conducted by the Gerep Environment’s research bureau on behalf of ONAS. The study revealed that the best strategy to protect Oued and reduce pollution in the southern suburb is to ensure a tertiary treatment of wastewater and guarantee its discharge into the sea through a pipe located 7km from the coast.

A similar project implemented in Raoued in 2018 was presented by ONAS as a success, given the enhanced quality of swimming water – a key environmental indicator to be highlighted. The project cost 80 million dinars and was implemented by Tunisian and Portuguese companies. The southern Meliane sanitation center and the sea outfall is expected to cost around 250 million dinars. This transition to tertiary treatment falls under the national sanitation strategy adopted by the governments of Habib Essid and Youssef Chahed between 2014 and 2019.

The rehabilitation and development of sanitation systems

As a first step, the municipalities of Bir al Mashariqah, Khalidia, and West Djebel – which directly discharge their wastewater into Oued – will be connected to the ONAS network through the establishment of a new purification plant in Khalidia. The first part of the project will cost 50 million dinars. Studies have already been carried out, and in 2022, calls for tenders will be published.

The second step is the renovation of the southern Meliane pumping station, which will receive 90,000m3 per day. This project will cost 135 million dinars. The Meliane pumping station was inaugurated in 1979. For Sihem Sajni, a senior engineer at the ONAS, “the station’s age is a contributing factor as to why effluents are off-spec.”

The third phase, expected to take place in 2023 and is funded by German Bank KFW, relates to the treatment of industrial effluents of the integrated treatment plant of Rades.

Finally, ONAS will develop the marine outfall project located 7km from the coast at a depth of 12m with a part on the ground from the Rades plant. Expected ONAS interventions in the governorate of Ben Arous are shown on this map created after the 9 November meeting in Ezzahara.

Southern Meliane Marine Outfall Project

Tertiary treatment favors the reuse of wastewater. ONAS is looking to reuse the majority of treated wastewater and to discharge a small amount (15%) into the sea. During the meeting, the ONAS Director-General presented examples for reusing wastewater in line with those adopted following the implementation of an outfall in the northern suburb of Tunis. For example, in the northern suburb, a developer had expected to spend 4 million dinars in order to pump water from the Chotrana plant to irrigate the golf course in the residential development of Raoued.

This project was believed to be the best solution among all possible scenarios. Yet, during the discussion, participants raised other possibilities, such as the use of treated wastewater to recharge the phreatic zone and in agriculture. They questioned the benefit of spending that much to discharge unpolluted and compliant water.

The environmental remediation of the contaminated space will be undertaken in two stages. First and progressively, halting daily pollution flows will enable water currents and the flora to provide a regenerative role. Environmental remediation projects must be considered to hope for the southern suburb of tomorrow that will look more like the one that existed before the damage done by ONAS. All stakeholders are responsible for environmental remediation and biodiversity restorations. This includes factories that contribute to the deterioration of the environment and equipment, ministries, and public protection agencies.

Recommendations by residents for the southern coastline

As long as wastewater is being discharged daily without cleaning up the sea, swimming in the southern suburb poses a health risk and should be banned. Signs are necessary to that effect.

The Ministry of Environment is mandated to protect the environment. However, since ONAS is producing the highest amount of polluted water in the country, its affiliation with the Ministry of Environment is paradoxical. Transferring the mandate of ONAS to another ministry may enable better supervision of its activities.

As long as industrial actors fail to undertake pretreatment, which is provided for in their tender specifications, irreversible and dangerous chemical contamination of the sea will continue. These dangers will also continue as long as the decisions of ANPE and APAL agents are not implemented. Stricter enforcement of regulations may help mitigate this problem.

Other infrastructures on the coast that are hazardous should also be removed, such as the dams that contribute to the proliferation of algae and produce foul smells.

Rades Port control is also necessary. Banning the oil changes and degassing of incoming ships will also help lower the current pollution rates in the natural environment.

The views represented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arab Reform Initiative, its staff, or its board.