Introduction

In October 2019, the results of legislative elections in Tunisia produced a fragmented parliament consisting of parliamentarians representing 30 different electoral lists. This splintered legislature posed difficulties for both government formation and effective decision-making. The Ennahdha Party secured a plurality of seats but with only 52 of 217, it struggled to form a government. Instead, temporary alliances between parties and parliamentary blocs were formed. Ineffective governance and constant infighting led to a rapid decline in both the popularity of both the parliament, as an institution, and the parliamentarians, as individuals. The coalitions were diverse and lacked a common purpose. This left citizens frustrated and disillusioned which increased their nostalgia for the decisiveness of the previous, authoritarian system. This widespread disdain for the People’s Assembly of Representatives helped lay the ground for President Kais Saied’s autocoup on July 25.

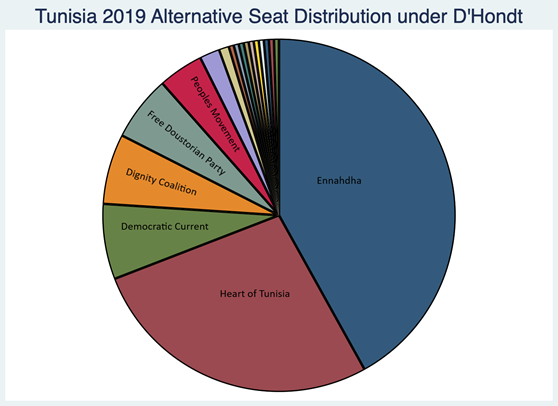

Although voter behaviour on election day can be attributed to a range of factors, the electoral formula, the mathematical equation that controls how votes are converted into seats in the legislature, is a key determining factor in election outcomes. This paper demonstrates how replacing the HQLR formula with either the D’Hondt or St.Lague divisors formula would be a minor adjustment with a significant impact. The Hare Quota-Largest Remainders (HQLR) formula promoted consensus-building during Tunisia’s constitution-writing process and in the new democratic regime’s first years but it has gradually become an obstacle to democratic consolidation.

Tunisia must undertake numerous reforms to consolidate its democratic gains, such as establishing a constitutional court and ensuring stricter oversight and accountability mechanisms, but changing the electoral formula would be a highly impactful and easily implementable ‘quick win’.

Proportional Representation and Hare Quota-Largest Remainders (HQLR) formula

Tunisia’s legislative elections use a closed-list proportional representation (PR) system. This ensures each electoral district is represented by several members of parliament. For example, the highly populated electoral districts of Ben Arous and Sousse are represented by 10 parliamentarians while the more sparsely populated districts of Tozeur and Tataouine are represented by 4. Voters choose one party or independent candidate list; they cannot select individuals.

This electoral system also requires an electoral formula that converts votes to seats. The formula used for 2011, 2014, and 2019 Tunisia legislative elections is the Hare Quota-Largest Remainders (HQLR). In 2011, the High Commission for the Fulfillment of Revolutionary Goals, Political Reform, and Democratic Transition (HCFRG), the temporary Tunisian legislature until the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) could be held in October, decided that the HQLR formula was most suitable. This proved to be an excellent decision for the time. HQLR is accommodating to small parties which is the ideal electoral system choice for a state grappling with an authoritarian legacy. It ensured voices were not marginalised during the critical moment of consensus-building needed to establish a constitution.

In the wake of Ben Ali’s overthrow, the shape of Tunisia’s party system was highly uncertain. The only large party with a national organization was Ennahdha. Other actors lacked information about their own electoral viability but shared an interest in preventing Ennahdha from dominating the constitution-writing process to “ensure that the monopolistic control by one party of any constituency, as under Ben Ali, could never be replicated.” Maya Jribi, of the Progressive Democratic Party, argued that the preference for a largest remainder system/formula was because “[the electoral system] has to allow a large representativity in the parliament” . The use of HQLR in 2011 meant that it was “easier for small parties to win seats by requiring fewer votes to win a seat compared with other democratic electoral systems” . As Ennahdha was short of the 109-seat absolute majority required to vote on an incoming government and to pass organic laws, it formed a three-party “Troika” coalition with Congress for Republic and Ettakatol. This coalition “gave assurances to various sides that no party could unilaterally make binding decisions and also gave all incentives to remain engaged in the institutional process” .

If Tunisia had used the D'Hondt formula in 2011, under the same distribution of votes Ennahdha would have had 69% of the NCA seats and could have written the new constitution in “whatever language it wanted” as there would have been “substantially less incentive for deliberation and compromise” . Instead, thanks to the use of HQLR, Ennahdha was the largest party but with a reduced representation. This ensured that “Tunisia’s constitutional moment would be characterized by negotiation among diverse parties and groups rather than imposition by the dominant party” . The relatively effective cooperation of these parties facilitated the initial establishment of democratic institutions . In short, HQLR was the ideal formula for the constitution-writing process.

2014 to 2019: too much consensus, not enough reform.

The HQLR formula was used in the 2014 Assembly of the People's Representatives (ARP) elections. At the time, it appeared to be the right decision to use this formula again because it encouraged parties to collaborate which supported the democratic transition. However, the experience of the 2014-2019 period suggests that HQLR’s value was temporary and that in the long term it may be detrimental to democratic consolidation.

Nida Tounes, Ennahdha’s secularist opponents, won 37.6% of the votes and were awarded 86 seats. This prevented Nida from governing alone. The absence of an outright winner encouraged the formation of national unity governments which included two dominant parties, Ennahdha and Nida Tounes. Had D'Hondt been used Nida would have won 116 (53%) parliamentary seats. Instead, the HQLR formula ensured that Nida was twenty-three seats short of the absolute majority needed to form a government by itself. Nida opted to form a unity government with Ennahdha, the very party they aimed to prevent from dominating Tunisian politics, in addition to the Free Patriotic Union (UPL) and centre-right Horizons of Tunisia. On 5 February 2015, HoG Habib Essid’s cabinet was approved by parliament 166-30. Four of the top five parties, holding 82% of the assembly’s seats among them, were now in government together. The absence of any viable parliamentary opposition was oddly analogous to the one-party state Tunisia’s 2010 uprising sought to dislodge. Boubekeur described this arrangement as “bargained competition” with “Islamists and old regime elites bargaining on their mutual reintegration and their monopolization of the post-revolutionary political scene while fiercely competing over political resources through various (often informal) power-sharing arrangements.”

The coalition between Ennahdha and Nida Tounes initially had a stabilizing effect in the nascent democracy. However, this marriage of convenience increasingly became a problem when facing the difficult but necessary task of comprehensively debating bills for systematic reforms. For example, the absence of a discernible legislative opposition meant that laws that contained anti-democratic elements, such as the 2015 counterterrorism law and the 2017 Economic Reconciliation Bill, as known as the reconciliation law, were passed by elite compromise with insufficient scrutiny.

The counterterrorism law (no.26 of 2015) which allows terror suspects to be held without charges for 15 days, weakens due process, and permits the death penalty, was passed with 174 out of 217 votes. Lawmakers who critiqued the text chose not to vote against it in fear of being labelled terrorist sympathisers. Yet state-run newspapers accused the 10 MPs who abstained from voting, in addition to human rights organizations that expressed concerns, of supporting terrorism.

Our proposition is that, had Tunisia used a different electoral formula in 2014 — one that delivered a larger winner’s bonus and less party fragmentation – Ennhadha would likely have been in opposition rather than part of a national unity coalition. The motivation for opposition parties to provide scrutiny and resistance to government initiatives is greater than for members of the governing coalition. In Ennahdha’s case, the party’s historical experience of persecution under as a nominal terrorist threat during the Ben Ali era might especially have fueled dissent with respect to the proposed legislation. We expect, therefore, that a parliament elected using the D’Hondt or St. Lague divisor rule could have delivered more substantive debate on the content of counter-terrorism law. We appreciate that our proposal is speculative, but we think our electoral simulations illustrate reasonable grounds for such conjecture.

Regarding transitional justice, Nida presented the Economic Reconciliation Bill (ERB) in September 2017 to “grant amnesty to corrupt businessmen as well as state officials accused of financial corruption and misuse of state funds – as long as they repay the stolen money” . Although Ennahdha initially rejected the ERB, it chose to “remain aloof on debates around the process, as it would jeopardize its alliance with Nidaa.” Likewise, while Nida consistently opposed the work of the Truth and Dignity Commission, Ghannouchi reneged on previous calls to “purge” key ministries to maintain the unity government. These elite bargaining arrangements “contributed to public disillusionment with political parties and democracy.”

HQLR prevented the formation of both an effective government and a coherent parliamentary opposition, leading to decision-making based on elite compromises rather than rigorous debate in parliament.

Al Jazeera’s Nazannine Moshiri characterized the situation as follows: “The main two parties in the country are now in government, and also the two other smaller parties which are quite popular here, that has weakened the opposition and a lot of people are saying this is almost like a one-party state.” Moshiri’s analogy with a one-party state is hyperbolic but his broader point underscores our argument that the national unity government, and correspondingly weak parliamentary opposition, meant that decisions made by Nida-Nahda were by elite consensus rather than being scrutinised by an adversarial parliamentary debate between government and opposition.

The 2019 fragmented parliament to the July 2021 autocoup

The 2019 election results produced Tunisia’s most fragmented parliament yet. Both Ennahdha and Nida were punished at the ballot box for their elite power-sharing and political compromise arrangements. Ennahdha finished first, but with only 19.6% of the vote, it won 52 seats, its lowest post-2011 result. Nida, which had splintered into serval parties since 2014, captured only 3 seats compared to 86 in 2014. Parties that won few seats in 2014 were more successful in 2019, such as the Free Doustourian Party (17), Democratic Current (22), and People's Movement (15). Also, several new parties were successful, including Heart of Tunisia (38), Dignity Coalition (21) and Long Live Tunisia (14). In addition, 12 different parties accounted for 25 seats; Project Tunisia (4), Mercy Party (4), Republican Popular Union (3), Tunisian Alternative (3), Nida Tounes (3), Horizons of Tunisia (2), plus 6 that won just 1 seat each. 13 additional seats went to independent list candidates. Therefore, the parliamentary seats were awarded to a plethora of parties.

This fragmentation also manifested at electoral district level. The 10 parliamentarians representing the Ben Arous district were from eight different party lists: the Heart of Tunisia (2), Ennahdha (2), Free Doustourian Party (1) Democratic Current (1) Dignity Coalition (1) Mercy Party (1) Long Live Tunisia (1), and Popular Republican Union (1) party lists.

By 2019, opposition to opportunistic government coalitions of convenience had emerged as a prominent theme in Tunisian politics. The unity coalitions of the 2014-2019 period, where Ennahdha secured its integration into the state at the expense of its ideological commitments and Nida secured access to state resources such as public procurement and ministerial appointments, became targets of criticism. Although ideologically distinct, the Free Doustourian Party (FDP) and Dignity Coalition campaigned on a common theme of resentment among voters “who do not accept the logic of tactical convergence of opposing parties.” The FDP’s relative electoral success is partly due to party leader Abir Moussi’s principled refusal to coalesce with Ennahdha. In comparison, Ennahdha was rejected by part of its grassroots for its leaders’ openness to considering an alliance with the FDP; “this was perceived as the pinnacle of cynicism among voters.” Yet the need for coalition only grew with Tunisia’s increased party system fragmentation.

But the continued use of HQLR was inhibiting Tunisia’s party system from developing. Instead, HQLR produced results that encouraged improvisation in the establishment, between elections, of parliamentary voting blocs for purposes of bargaining over government ministries and other spoils.

Parliamentary fragmentation posed serious problems for both government formation and effective decision-making. Ennahdha selected Habib Jemli as Head of Government. His proposed cabinet failed to receive majority support because parliamentarians thought it contained too many pro-Ennahdha ministers. After Jemli’s failure, President Kais Said shifted formateur authority to Elyes Fakhfakh, a member of the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties Party and former Minister of Tourism. A second failure would have prompted new elections. Therefore, MPs accepted Fakhfakh’s eclectic coalition government consisting of Ennahdha, Nida Tounes, Democratic Current, Long Live Tunisia, The People’s Movement, and Tunisian Alternative. This coalition was agreed not because there was a coherent reason for collaboration, but because the newly-elected MPs did not want to lose their seats.

Change the formula, not the system

President Saied is correct that Tunisia’s democratic transition has stalled and the parliament is an unpopular institution. However, arguing that a directly elected national legislature is unnecessary will jeopardize Tunisia’s democratic status. Said’s proposed political reforms seek to prioritise the role of local democracy at the expense of political parties and national level legislative elections. If his plans for legislative reform are implemented, elections will only occur at the presidential and local council, in each of Tunisia’s 265 delegations, levels. The national level parliament will instead be selected through hierarchical escalation from regional councils, which were selected by lot at the delegation level.

There is little empirical evidence to support the democratic reliability of a system that marginalises the influence of political parties. Citizen skepticism toward legislatures and disillusionment with political parties are common in democracies, but attacks on legislatures and efforts to purge parties from politics are moves more closely associated with budding autocrats than with democratic reformers. In Latin America, both Peru’s Alberto Fujimori, in the early 1990s, and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez, a decade later, railed against party systems they characterized as corrupt and feckless, used extra-constitutional means to close down national legislatures, and proceeded to build political regimes that centralized power in the presidency. Both presidents did lasting damage to their countries’ democratic institutions.

Although political parties are not perfect, party democracy “outperforms pluralist democracy in terms of predictability of policy outcomes.” Tunisia already uses PR, which ensures a multiplicity of political views are represented. PR also prevents the emergence of a two-party system that would divide the general will . The current system could produce a considerably more effective and accountable government if the electoral formula is changed. This would also forego the need for Saied’s complex, bottom-up system.

Winners and Losers

A democratic election should produce a clear distinction between winners and losers. If the party that ‘wins’ the election can form a coherent coalition, or govern by itself, it is therefore accountable for any successes or failures. Meanwhile, electoral losers typically become minorities partners in the ruling coalition or provide horizontal accountability forming the parliamentary opposition. The fragmentation fostered by HQLR blurs the lines between electoral winners and losers, allowing parties that form ruling coalitions to avoid responsibility. Despite Ennahdha gaining pluralities in the 2011 and 2019 elections, and being part of unity coalitions from 2014-2019, the persistent fragmentation of parliament encouraged the party to deflect responsibility for government performance, framing itself as in opposition to governments in which it participated.

Moreover, consensus-based governance stifles dialogue. The 2014-2019 proved how unity-government parties preferred to maintain stability and avoid challenging and polarizing debates rather than engage in rigorous discussion regarding the necessary and difficult issues facing post-revolution Tunisia.

Simulated D’Hondt and St.Lague results

While HQLR was effective for inclusive constitution writing, its continued use is detrimental to democratic consolidation. In Hong Kong, its use caused alliances to splinter into factions because HQLR rewards smaller parties. In Colombia, HQLR was “an obstacle to the development of common policy platforms and effective governance.” Realising the damage that the formula was causing, a set of electoral reforms in 2004 replaced HQLR with D’Hondt.

D’Hondt is the most-used PR formulas among democracies worldwide and among post-transition democracies for founding elections. The use of D’Hondt in Tunisia would have important implications for election outcomes, namely it should encourage those running for office, parties and independent lists, to behave differently. These election simulations use the D’Hondt and St.Lague formulas on the same election results.The D’Hondt or St.Lague divisor systems give the largest parties the largest seat bonuses. D’Hondt rewards the largest parties more than St.Lague, but both formulas ensure parties with a larger share of votes gain a larger number of seats than HQLR.

Changing the formula would encourage unsuccessful political actors to merge into larger and more coherent parties. Over a few election cycles, this change can support the consolidation of the Tunisian party system. The HQLR formula provides no incentive to merge. Correspondingly, Tunisia has seen continued growth in the number of registered parties. Over 100 political parties participated in the 2011 NCA elections and by 2020 over 200 parties were registered.

Conclusion

The HQLR formula was ideal in 2011 when the initial challenge facing Tunisian democracy was ensuring the constitution-writing process was highly inclusive. By mitigating larger parties’ seat bonuses, HQLR contributed to a power-sharing arrangement that supported the early phases of a transition to democracy and it ensured pluralism at the country’s constitutional moment. However, national unity government arrangements amongst parties with different political ideologies after 2014 proved to be obstacles to further democratic consolidation.

We acknowledge that our argument implies a conundrum. If HQLR is critical when a new democracy’s survival depends on buy-in across the widest possible range of political actors, but detrimental to long-term governance, then how can we identify the moment when the asset turns into a liability, and the political leaders should replace HQLR? The ideal, we suggest, would be an agreement is made during the initial transition to democracy, under which the first X elections (where X could be 1, 2, or 3) are to be held under HQLR after which the system shifts to a formula that rewards size (for example, D’Hondt or St. Lague). The heightened uncertainty of democratic transitions, coupled with the surfeit of confidence with which politicians are often endowed, make it possible to imagine party leaders pre-committing to such a sequence.

Tunisia, however, is past that moment of uncertainty and optimism. The relative strengths, and limitations, of the country’s main political actors are now known and the shelter that HQLR provides to the electorally weak undoubtedly appeals to many incumbents. But recent experience also highlights the current system’s precarity. Tunisian democracy is threatened by elections that produce useless coalitions. The country does not need to abandon the national level parliamentary democracy or proportional representation. It should, however, change the electoral formula to either D’Hondt or St.Lague divisors formulas as these would prevent parliamentary fragmentation, would encourage the development of a coherent political party landscape, and would make electoral winners accountable for their term in office/power.

Table 1: 2019 election results and simulated results

|

Number of Seats |

| List |

Vote share % |

HQLR |

D'Hondt |

St Lague |

| Ennahdha |

19.5 |

52 |

91 |

71 |

| Heart of Tunisia |

14.5 |

38 |

59 |

45 |

| Democratic Current |

6.4 |

22 |

14 |

18 |

| Dignity Coalition |

5.9 |

21 |

15 |

18 |

| Free Doustourian Party |

6.6 |

17 |

13 |

19 |

| The People's Movement |

4.5 |

15 |

9 |

11 |

| Long Live Tunisia |

4.1 |

14 |

4 |

9 |

| Project Tunisia |

1.4 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| The Mercy Party |

1.2 |

4 |

1 |

4 |

| Republican Popular Union |

2.0 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

| Tunisian Alternative |

1.6 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

| Nida Tounes |

1.5 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

| Hope and Work |

1.6 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

| Horizons of Tunisia |

1.5 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

| Aich Tounsi |

1.5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Popular Front |

1.1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Social Democratic Union |

1.0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| The Love Current |

0.6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Socialist Doustourian Party |

0.6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| The Farmers' Voice |

0.3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| We are Here |

0.3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Keeping the Promise |

0.2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Independent Youth |

0.2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| The Excellence |

0.2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| The Green League |

0.2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Back to the Origins |

0.1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| The Goodness |

0.1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Hard Work and Giving |

0.1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Citizenship and Development |

0.1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Siliana in our Eyes |

0.1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| We are all Tunisians |

0.0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

References

Abderrahmen, Aymen. ‘How Tunisia’s “Two Sheikhs” Sought to Halt Transitional Justice’. Tahiri Institue Middle East Policy, December 2018. https://timep.org/commentary/analysis/how-tunisias-two-sheikhs-sought-to-halt-transitional-justice/.

Ahram Online. ‘Tunisia MPs Approve Landmark New Govt’. Ahram Online, 5 February 2015. https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/2/8/122290/World/Region/Tunisia-MPs-approve-landmark-new-govt.aspx.

Al Jazeera. ‘Tunisia Parliament Approves Unity Government’, 6 February 2015. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/2/6/tunisia-parliament-approves-unity-government.

———. ‘Tunisia Parliament Rejects Gov’t of PM-Designate Habib Jemli’, 11 January 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/1/11/tunisia-parliament-rejects-govt-of-pm-designate-habib-jemli.

Boubekeur, Amel. ‘Islamists, Secularists and Old Regime Elites in Tunisia: Bargained Competition’. Mediterranean Politics 21, no. 1 (2 January 2016): 107–27.

Carey, John M. ‘Electoral Formula and Fragmentation in Hong Kong’. Journal of East Asian Studies 17, no. 2 (2017): 215–31. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-east-asian-studies/article/electoral-formula-and-fragmentation-in-hong-kong/C74B4E8FC20A49A0877E561D13F8B268.

———. ‘Electoral Formula and the Tunisian Constituent Assembly.’ Dartmouth College, 2013. http://sites.dartmouth.edu/jcarey/files/2013/02/Tunisia-Electoral-Formula-Carey-May-2013-reduced.pdf.

———. ‘Electoral System Design in New Democracies’. In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, edited by Erik S Herron, Robert J Pekkanen, and Matthew S Shugart, 2018.

Carey, John M., Tarek Masoud, and Andrew Reynolds. ‘Institutions as Causes and Effects: North African Electoral Systems During the Arab Spring’. HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-042, 2015. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/institutions-causes-and-effects-north-african-electoral-systems-during-arab-spring.

Cimini, Giulia. ‘Parties in an Era of Change: Membership in the (Re-)Making in Post-Revolutionary Tunisia’. The Journal of North African Studies 25, no. 6 (2020): 960–79. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ref/10.1080/13629387.2019.1644918.

Corrales, Javier, and Michael Penfold. Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chavez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015.

Cristiani, Dario. ‘Tunisia’s Political Landscape a Decade after the Jasmine Revolution’. Atlantic Council, 17 December 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/tunisias-political-landscape-a-decade-after-the-jasmine-revolution/.

Dejoui, Nadia. ‘Le PDL refuse toute prise de contact avec Ennahdha’. L’Economiste Maghrébin, 17 October 2019. https://www.leconomistemaghrebin.com/2019/10/17/pdl-refuse-toute-prise-contact-ennahdha/.

France 24. ‘Tunisian Parliament Gives Vote of Confidence to Coalition Government’. France 24, 27 February 2020. https://www.france24.com/en/20200227-tunisia-parliament-coalition-government-elyes-fakhfakh-ennahda.

Hamid, Shadi, and Sharan Grewal. ‘The Dark Side of Consensus in Tunisia: Lessons from 2015-2019’. Brookings, 31 January 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-dark-side-of-consensus-in-tunisia-lessons-from-2015-2019/.

Human Rights Watch. ‘Tunisia: Flaws in Revised Counterterrorism Bill’. Human Rights Watch, 7 July 2015. https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/07/07/tunisia-flaws-revised-counterterrorism-bill.

Jebli, Hanen. ‘How a Battle inside This Tunisian Political Party Is Paralysing the Country’. Middle East Eye, 2018. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/how-battle-inside-tunisian-political-party-paralysing-country.

Kölln, Ann-Kristin. ‘The Value of Political Parties to Representative Democracy’. European Political Science Review 7, no. 4 (November 2015): 593–613. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-political-science-review/article/abs/value-of-political-parties-to-representative-democracy/F019B8C30DC43868D8FB4E81FFC267F7.

Lust, Ellen, and David Waldner. ‘Parties in Transitional Democracies: Authoritarian Legacies and Post-Authoritarian Challenges in the Middle East and North Africa’. In Parties, Movements, and Democracy in the Developing World, edited by Nancy Bermeo and Deborah J. Yashar, 157–89. Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

McClintock, Cynthia. ‘Peru’s Fujimori: A Caudillo Derails Democracy’. Current History 92, no. 572 (1993): 112–19.

Meddeb, Hamza. Email, 29 September 2021.

Mersch, Sarah. ‘Tunisia’s Ineffective Counterterrorism Law’. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 6 August 2015. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/60958.

Murphy, Emma C. ‘The Tunisian Elections of October 2011: A Democratic Consensus’. The Journal of North African Studies 18, no. 2 (1 March 2013): 231–47.

Pickard, Duncan. ‘Prospects for Implementing Democracy in Tunisia’. Mediterranean Politics 19, no. 2 (4 May 2014): 259–64. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13629395.2014.917796.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Du contrat social; ou Principes du droit politique (Éd.1762). Paris: Hachette Livre, 2012.

Shugart, Matthew, Erika Moreno Soberg, and Luis E. Fajardo. ‘Deepening Democracy by Renovating Political Practices: The Struggle for Electoral Reform in Colombia.’ In Peace, Democracy, and Human Rights in Colombia, edited by Christopher Welna and Gustavo Gallón, 202–67. Kellogg Institute Series on Democracy and Development. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2007.

Yardımcı-Geyikçi, Şebnem, and Özlem Tür. ‘Rethinking the Tunisian Miracle: A Party Politics View’. Democratization 25, no. 5 (4 July 2018): 787–803.

The views represented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arab Reform Initiative, its staff, or its board.