*This piece is published in collaboration with Chatham House. It is part of a series which addresses the future of governance and security in the Middle East and North Africa, and their impact on the role of the state in the region.

The state’s control of oil rents underpinned Iraq’s post-2003 political order, characterized by Muhasasa Ta’ifia or sectarian apportionment. It enabled the political order’s continuity and apparent stability through multiple crises, including the 2008 financial crisis and the war with ISIS. However, the crash in oil rents, brought about by COVID-19’s disruption of the world economy, exposes the structural inconsistencies and inherent contradictions of the Muhasasa Ta’ifia system and its singular dependence on a volatile resource. The political order’s response to the current crisis – by focusing on maintaining public expenditures at the expense of investment spending – mirrors its responses to previous crises. However, this time around, its current institutional decay is extremely advanced, and oil dynamics have fundamentally changed. So, will the COVID-19 mark the endgame of the Muhasasa system?

Anatomy of the Muhasasa: Bloating the public sector

The Muhasasa Ta’ifia involves the control of state resources by an inclusive government of all ethno-sectarian parties, in proportion to the seats won by each party in parliamentary elections. This leads to fierce competition for power and influence through developing party patronage networks. Public sector employment became a primary means for building such networks because of its dominance in the economy and its role as the largest formal employer.

This, enabled by rising oil rents, led to a dramatic expansion in the number of public sector employees, whose expenditures increased almost fivefold from 2005 to an estimated $50bn in 2020 (red line in Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Dotted lines are projection ranges, expenditure trend line is in lighter colour (for details see sources section below)

Figure 1 - Dotted lines are projection ranges, expenditure trend line is in lighter colour (for details see sources section below)

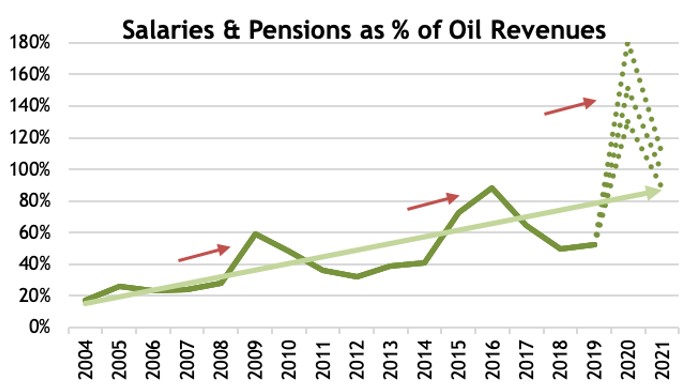

These expenditures increased consistently, pausing only when oil revenues declined during crises, but resuming their upward trend as the crisis passed. In the process, they consumed an ever-increasing percentage share of oil revenues – a share that spiked successively and unsustainably higher during each crisis as oil revenues plunged (red arrows in Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Dotted lines are projection ranges, expenditure percentage trendline is in lighter colour (for details see sources section below)

Figure 2 - Dotted lines are projection ranges, expenditure percentage trendline is in lighter colour (for details see sources section below)

Such expenditure by successive governments came at the expense of spending on much needed public infrastructure (destroyed by over four decades of conflict) and of building the country’s capital stock – both essential foundations of sustainable economic growth. This misspending, the state’s weakness in enforcing the rule of law, its stifling bureaucracy, and its central role in the non-oil economy through the control of oil rents – itself another vehicle for the extension of party patronage networks – have all inhibited the formal private sector’s growth and its ability to generate good jobs. Accordingly, large parts of the country’s private sector development took place in the informal economy, which increasingly became the source of livelihood for the poor and marginalized segments of society who currently account for 20.5% (2017/2018) of the population.

The country’s demographic pressures (Figure 3) generate ever-growing cohorts of job seekers but neither the bloated public sector nor the stunted formal private sector can absorb these rising number of young job seekers, which leaves most of them dependent on the informal economy for their livelihood and its ensuing constraints on their social mobility and financial security. Within the official unemployment figures of 9.8%, youth unemployment, for those aged 15-24, stands at 16.5%, while surveys reveal only 6% of the country’s youth are satisfied with government efforts to improve employment opportunities. In such an economy, demonstrations demanding jobs and reform become inevitable, and as expected the first wave of the October 2019 demonstrations was composed of young men and women seeking jobs and was ignited by the government’s crackdown on the informal sector earlier in the summer.

Figure 3 - Source: IMF Iraq Country Report 19/248

Figure 3 - Source: IMF Iraq Country Report 19/248

COVID-19’s impact on Iraq’s Muhasasa system

The disruptions of COVID-19 to the global economy, and its impact on lowering oil prices, present a new type of challenge to Iraq and to the outlook of the Muhasasa Ta’ifia’s governance model which has grown dependent on public job creation as a way to acquire legitimacy.

Forecasting the impact of COVID-19 crisis on Iraq is fraught with uncertainty, yet it is possible to sketch broad trends. The nature of the virus precludes a return to full normality for the world economy for the foreseeable future. Even though global lockdowns are expected to ease over the next few months, world demand for oil is expected to remain low until at least the end of 2020 (Figure 4). Under this scenario oil prices, as measured by Brent crude, are projected to average between $30-40 per barrel over the next 12 months, and between $45-55 per barrel over the succeeding 12 months.

Figure 4 - Source: International Energy Agency (IEA)

Figure 4 - Source: International Energy Agency (IEA)

As in the previous crises of 2008 and 2014, the governing elite will aim to maintain expenditures on salaries, pensions and social security, but also embark on dramatic cuts to investment spending plans and to expenditures on goods and services, as seen from the government’s early responses to the unfolding crises. However, these reduced expenditures will not be enough to offset losses in oil revenues. Each $1 drop in Brent crude prices reduces oil revenues by about $1.25bn, leading to an estimated deficit in a range of $41.5 to 52.5bn for the next 12 months. This deficit will initially be funded domestically through indirect monetary financing, using the country’s foreign reserves, which were $63.7bn as of the end of February. However, this approach requires near-ideal scenarios to be effective, as it does not allow for lower oil prices than forecast, or for a delay in their expected recovery. A decline of these reserves to under $15bn could lead to a devaluation of the currency, which would lower the living standards of the majority of the population given Iraq’s high dependence on imports to satisfy consumption. The new government’s approach addresses the issues raised here head-on and would rebalance the budget’s structural imbalance. However, it has the herculean task of passing such a solution through Muhasas’s parliament, and an acceptance by an alienated population. Crucially a successful passage will start un-ravelling the patronage networks much sooner, and as such the governing elite will seek its derailment, pushing instead for a continuation of past practices. Beyond the next 12 months, expected higher oil revenues will remove much of the pressure on government finances, but with public sector payroll expenditures consuming the bulk of these revenues (Figure 4) and with the country’s foreign reserves depleted, the consequence will be a continuation of the lack public investments in infrastructure or reconstruction, and the maintenance of most cuts to spending on goods and services. This would exasperate the pressures on the informal economy, already hard hit by the disruptions of the COVID-19 lockdown and the government’s prior spending cuts.

This creates a multi-faceted challenge that the political elite, with its increasing fragmentation and the erosion of its legitimacy over the years, is ill-equipped to resolve. The size of the public sector payroll expenditures leaves no room for new hires nor for infrastructure and reconstruction spending. While resorting to loans to fund public investments could be an option, this means a foreign borrowing supported by an IMF accord along the lines of the 2016 Stand-By Agreement as Iraq would have likely exhausted domestic sources of borrowing in the first 12 months. Such foreign loans would come with conditions to embark on accelerated structural economic reforms and integrating the informal economy into the formal economy. They would also come with painful adjustments that require a buy-in by an alienated population, and they would undermine the foundations of patronage networks. Meanwhile, the economic conditions of the neglected informal economy that led to the 2019 demonstrations would have become progressively worse.

What next for Iraq? Damned If they do, dammed if they don’t

The post-2003 political order, for all its claims to be a departure from the past, is a decentralized evolution of the prior model under Saddam Hussain which has persistently expanded the patrimonial role of the state as a redistributor of oil wealth in exchange for social acquiescence of its rule. The system of Muhasasa Ta’ifia was already running out of steam and being challenged by the protest movements in 2018 and 2019. COVID-19 and its repercussions on the world economy have further exposed the current governance model and its dependence on volatile and declining oil rents as well as the inability of the current Iraqi political elites to manage their way out of the crisis.

Without real political reform that upends sectarian apportionment and in the process acquires legitimacy in the public’s eyes, the days of the Muhasasa Ta’ifia are running out, whether brought about by the current crisis or temporarily postponed by a quick recovery in oil prices. Without the fuel of ever sharply increasing oil rents, the foundations of the Muhasasa model are crumbling. The political order’s only survival option is resorting to excessive coercion and repression of an ever-growing disenfranchised young population – itself an unsustainable survival mechanism given the country’s demographic pressures and the atomization of the political order.

Sources

The figures and charts cited in this article are the author’s estimates and are based on data from: the IMF Iraq country reports 2004-2019; The Ministry of Finance; the Ministry of Oil; The Ministry of Planning’s Central Statistical Organization (COSIT), the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI); and on publicly available news, analysis and research. Estimates for oil revenues for 2020 & 2021 take into account the coordinated OPEC+ deal agreed on 11 April but do not assume full compliance by Iraq with its quotas. Assumptions for budget spending for 2020 and 2021 are based on the author’s recent works as linked in the article, but updated to reflect the OPEC+ data. Total public sector expenditures are higher than that used here as they don’t include those for State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) employees as these are included in the transfers item in the budget but not broken down. All errors and omissions are the author's own.

Disclaimer

Ahmed Tabaqchali’s comments, opinions and analyses are personal views and are intended to be for informational purposes and general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any fund or security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax or investment advice. The information provided in this material is compiled from sources that are believed to be reliable, but no guarantee is made of its correctness, is rendered as at publication date and may change without notice and it is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding Iraq, the region, market or investment.

The views represented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Arab Reform Initiative, its staff, or its board.